Part 3: Database Engineering Fundamentals: MemCached In-Memory database Architecture

MemCached In-Memory database Architecture

Memcached Architecture

Memcached is an in-memory key-value store originally written in Perl and later rewritten in C. It is popular with companies such as Facebook, Netflix and Wikipedia for its simplicity.

While the word “simple” has lost its meaning when it comes to describing software, I think Memcached is one of the few remaining software that is truly simple. Memcached doesn’t try to have fancy features like persistence or rich data types. Even the distributed cache is the responsibility of the client not Memcached server.

Memcached backend has one job only, an in-memory key value store.

To Cache is a cop-out

Memcached is used as a cache for slow database queries or HTTP responses that are expensive to compute. While caching is critical for scalability, it should only be used as a last resort, let me explain.

I think running a cache for every encountered slow query is cop-out. I believe understanding the cause of performance degradation is key, otherwise the cache is just a duct-tape. If it is a database query, look at the plan, do you need an index? Are there a lot logic reads can you rewrite the query or include an additional filter predict to minimize the search space?

If it is an RPC, consider why are the calls chatty in the first place and can you eliminate the calls at the client side. Often times libraries and framework issue a fleet of queries when mis-used. Another reason black-boxes must be understood.

After running out of tuning options a cache might be needed, and that’s where Memcached is best suited for.

Memcached Architecture

In this article I’d like to do a deep dive into the architecture of Memcached and how the devs fought to keep it simple and feature-stripped. I’ll give my opinion on certain components that I believed should have been an option.

I’ll cover the following topics in this article.

- Memory Management

- Threading

- LRU

- Read/Writes

- Collisions

- Distributed Cache

- Demo

What is Memcached?

Memcached is a key-value store used as a cache. It is designed to be simple and is, therefore, limited in some ways. These limitations can also be looked at as features because they make Memcached transparent.

Keys in Memcached are strings, and they are limited to 250 characters. Values can be any type, but they are limited to 1 MB by default. Keys also have an expiration date or time to live (TTL). However, this should not be relied on, as the least recently used (LRU) algorithm may remove expired keys before they are accessed. Memcached is a good choice for caching expensive queries, but it should not be relied on for persistent or durable storage. Always build your application around Memcached not having what you want. Plan for the worse, hope for the best.

Memory Management

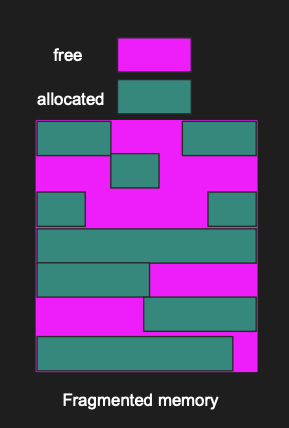

When allocating items like arrays, strings or integers, they usually go to random places in the process memory. This leaves small gaps of unused memory scattered across the physical memory, a problem referred to as fragmentation.

Fragmented memory

Fragmentation occurs when the gaps between allocated items continue to increase. This makes it difficult to find a contiguous block of memory that is large enough to hold new items. Technically there might be enough memory to hold the item but the memory is scattered all over the physical space.

Does that mean that the item fails to store if no contiguous memory exists? Not really, with the help of virtual memory, the OS gives the illusion that the app is using a contiguous block of memory. Behind the scenes, this block is mapped to tiny small areas in physical memory.

When fragmentation occurs, it can cause a program to run more slowly, as the system assembles the memory fragments. The cost of virtual memory mapping and the cost of multiple I/Os to fetch what could have been a single block of memory is relatively high. That is why we try to avoid memory fragmentation.

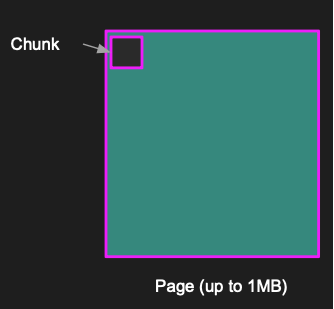

Memcached avoids fragmentation by pre-allocating 1 MB-sized memory pages, which is why values are capped to 1 MB by default.

Memcached allocates pages

The operating system thinks that Memcached is using the allocated memory, but Memcached isn’t storing anything in it yet. As new items are created, Memcached will write items to the allocated page forcing the items to be next to each other. This avoids fragmentation by moving memory management to Memcached instead of the OS.

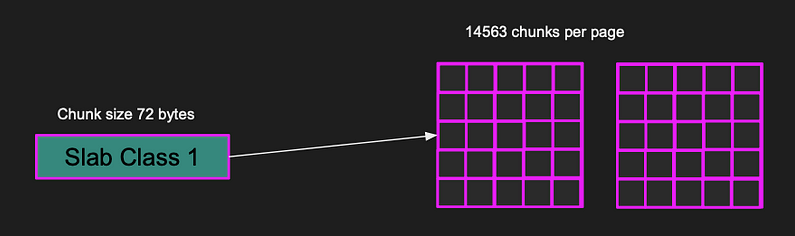

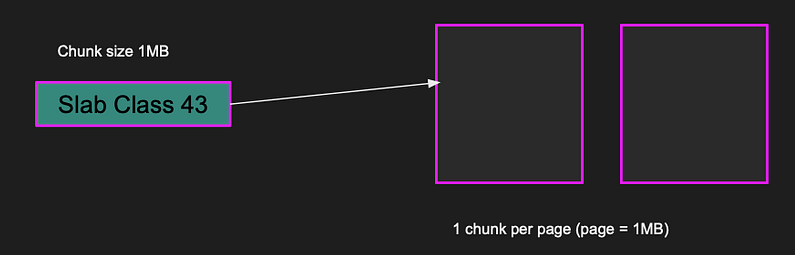

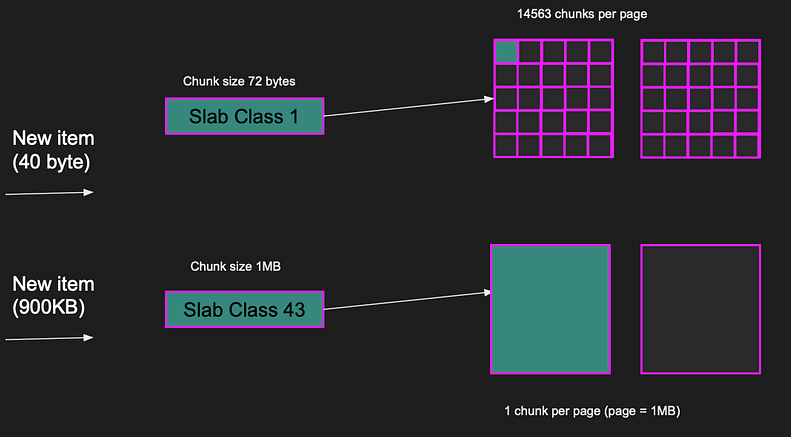

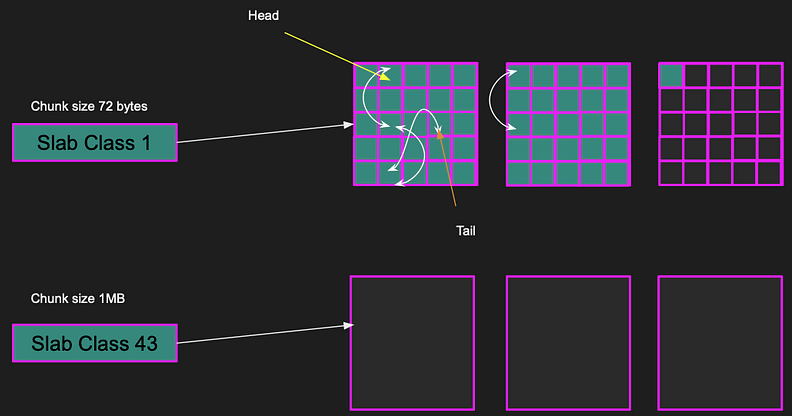

The pages are divided into equal size Chunks. The chunk has a fixed size determined by the slab class. A slab class defines the chunk size, for example Slab class 1 has a chunk size of 72 bytes while slab class 43 has a chunk size of a 1MB.

Pages of slab class 1 (72 bytes) stores 14563 chunks per page.

Pages of slab class 43 (1MB) stores 1 chunk per page

Items consistent of key, value and some metadata and they are stored in chunks. For example, If the item size is 40 bytes in size, a whole chunk is used to store the item. The closest chunk size to the 40 bytes item is 72 bytes which is slab class 1, leaving 32 bytes unused in chunk. That is why the client should be smart to pick items that fit nicely in chunks leaving as little unused space as possible.

Memcached tries to minimize the unused space by putting the item in the most appropriate slab class. Each slab class has multiple pages. Slab class 1, there are 14,563 chunks per page since each chunk is 72 bytes. If an item is less than or equal 72 bytes, it’ll fit nicely in the chunk. But if the item is larger, say 900 kilobytes, it doesn’t fit slab class 1. So, Memcached finds a slab class appropriate for the item. Slab class 43 of chunk size 1MB is the closest one, and the item will be put in that chunk. The entire item fits in a single page.

Note that we don’t need to allocate memory for the item because the memory is already pre-allocated.

Memcached fits items in the appropriate chunk size

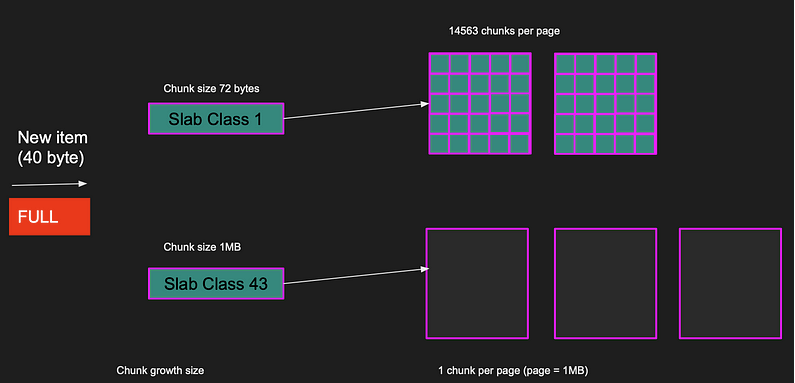

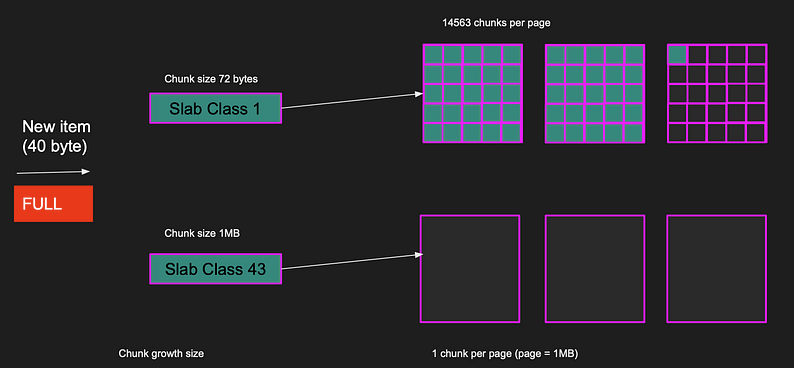

Let’s take a new example where there is a new item of size 40 bytes, but all allocated pages for this slab class are full, so the item can’t be inserted.

Slab class 1 is full

Memcached handles this by allocating a new page and storing the item in a free chunk.

A new page is allocated and the new item is placed

Threading

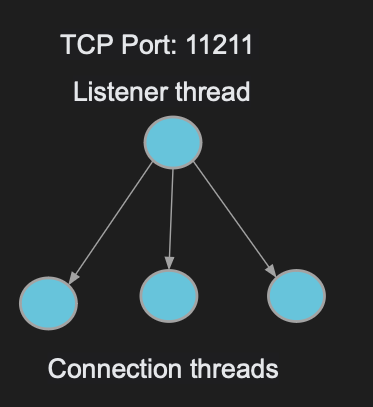

Memcached accepts remote clients, it has to have networking. Memcached uses TCP as its native transport they support. UDP is also supported but was disabled by default because of an attack that happened in 2018 called the reflection attack.

The Memcached listener thread creates a TCP socket to listen on port 11211. It has one thread that spins up and listens for incoming connections. This thread creates a socket and accepts incoming connections.

Memcached then distributes the connections to a pool of threads. When a new connection is established, Memcached allocates a thread from the pool and gives the connection file descriptor to that thread. That worker thread is now responsible of reading data from the connection.

If a stream of data or request to get a key is sent to the connection, the thread polls the file descriptor to read the request. Each thread can hosts one or more connections and the number of threads in the pool can be configured.

Listener thread accepts connection and distribute them to worker threads

Threading was more critical years ago when asynchronous workload wasn’t as abundant it is in 2022. You see when a thread reads from a connection, this operation used to be blocking in the early 2000s. The thread cannot do anything else until it gets the data. Engineers realized that this isn’t scalable and asynchronous I/O was born. Almost all read calls are now asynchronous, this means the thread can call read on one connection and move on to serve other connection.

However, the threading is still important in Memcached because read/write involves some CPU time in hashing and LRU computations. That one thread doing all this work for all connections might not scale.

LRU (Least Recently Used)

The problem with memory is it’s limited. If you store a lot of keys, even with good expiration dates, memory eventually fills up. What would you do when memory is full?

Well, you have two options as an architect.

- Block new inserts and return an error to the client to free some items

- Release old unused items

Memcached did the latter. This is where I wished they made this an option. It is as if I’m with the designers in the room arguing what to do. Having an LRU complicated Memcached and stripped it from its pure simplicity. The voice of reason has lost, and instead the client convenience won. Alas, it is what it is.

Memcached releases anything in memory that hasn’t been used for a very long time. That’s another reason why Memcached is called transient memory. Even if you set the expiration for an hour, you can’t rely on the key being there before the hour expires. It can be released at any time, which is another limitation (or feature!) of Memcached.

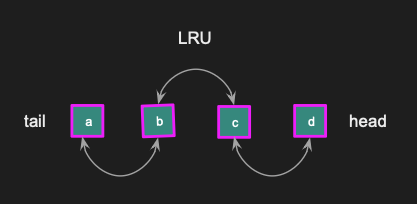

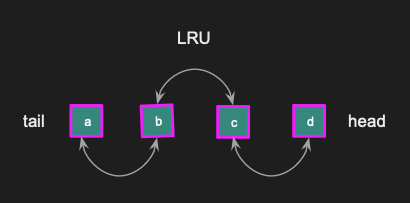

Memcached uses a data structure called a linked list LRU (Least recently used) to release items when memory is full. Every item in the Memcached key-value store is in the linked list, and every slab class has its own LRU.

If an item is accessed, it is moved from its current position to the head. This process is repeated every time an item is accessed. As a result, items that are not used frequently will be pushed down to the tail of the list and eventually removed if the memory becomes full.

LRU

Here is a big picture of the LRU cache. I derived this from reading the source code and the Memcached doc. In the diagram, we have pages and chunks. Each chunk is included in an LRU cache with a head and a tail pointer, and every item between the head and tail are linked to each other.

While the LRU is useful, it can also be quite costly in terms of performance. The locks that are necessary to maintain LRU can slow down throughput and complicate the application. If LRU was an option that could be disabled, Memcached could have remained simple. This would allow users to allocate a certain amount of memory to Memcached without having to worry about the overhead of managing LRU. The responsibility to free up items becomes the client’s.

LRU Locking

No two threads can update the same data structure concurrently. To solve this, the thread that needs to update any data structure in memory must obtain a mutex and other threads wait for the mutex to be freed. This is the basic locking model and it is used in all applications. Memcached is no different with the LRU data structures.

The original Memcached design had one global lock — all operations and LRU management were serialized rendering multi-threaded not as effective. As a result, clients could not access two different items at the same time, all reads were serialized.

Memcached fixed this by updating the locking model to LRU per slab class. This means clients can access two items from different slab classes without waits. However, they are still serialized when accessing two items from the same slab class because the LRU needs to get updated. This was later improved by minimizing the LRU updates to once every 60 seconds which allowed for multiple items to be accessed. However this wasn’t good enough.

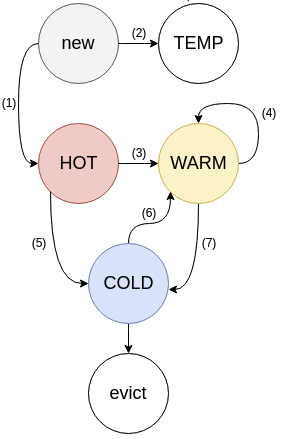

In 2018, Memcached completely redesigned the LRU to introduce sub-LRUs per slab class breaking it by temperature. This has significantly reduced locking and improved performance, but still the locking remained for items within the same temperature.

Memcached New LRU design (image memcached.org)

Now you know why I wished LRU was an option.

Reads and Writes

Reads

Let’s go through a read example in Memcached. To identify where the item lives in memory for a given key, Memcached uses hash tables. A hash table is an associative array. The beauty of an associative array is that it is consecutive, meaning that if you have an array of 1000 elements, accessing elements 7, 12, 24, 33, or 1 is just as fast because you know the index. Once you know the index, you can immediately go to that location in memory.

With hash tables, you don’t have an index — you have a key. The trick is to convert the key to an index and then access the element. We take the key and calculate its hash and do a modulus of the hash table size. Let us take an example

To read key “test” we hash “test” and then do modulus N where N is the size of the array of the hash table. This will give us a number between 0 and N — 1. This number can be used to index into the hash table and get the value for the key. This all happens in O(1) time.

The value of the key takes you to the page on the specific slab class for that item. When we read the value, we update the slab class LRU by pushing the item to the LRU head. This requires a mutex lock on the LRU data structure so multiple threads don’t corrupt the LRU.

Note that if two items are trying to be read of the same slab class, then the reads are serialized because the LRU needs to be locked.

Reading key “test”

When key test is read, and we get item d, the LRU is updated so that d is now in the head of the linked list.

d is at the head of LRU

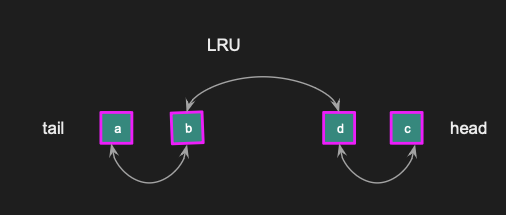

What happens if we read the key buzz pointing to item c? The LRU is updated so that c is now the head right after d.

c is now the head, followed by d

Writes

If we need to write a key with a new value of 44 bytes, we first need to calculate the hash and find its index in the hash table. If the index location is empty, a new pointer is created, and a slab class is allocated with a chunk. The item is then placed in memory, with the chunk fitting into the appropriate slab class.

Writing to key

Collisions

Because hashing maps keys to a fixed size, two keys may hash to the same index causing a collision. Let’s say I’m going to write a new key called “Nani”. The hash of “Nani” collides with another existing key.

To solve this, Memcached makes each index in the hash table map to a chain of items as opposed to the item directly. We add the key “Nani” to the chain which has now two items. When the key is read, all items in the chain need to be looked up to determine which one matches the desired key, giving us a O(N) at worse case. Here is an example

Write and Read Collision

Memcached measures the growth of these chains. If the growth is too excessive, read performance may suffer. To read a key the entire collision chain must be looked up to find actual key. The longer the collision chain, the slower the read.

If the performance of the reads starts to decrease, Memcached does a hash resize and shifts everything around to flatten the structure down.

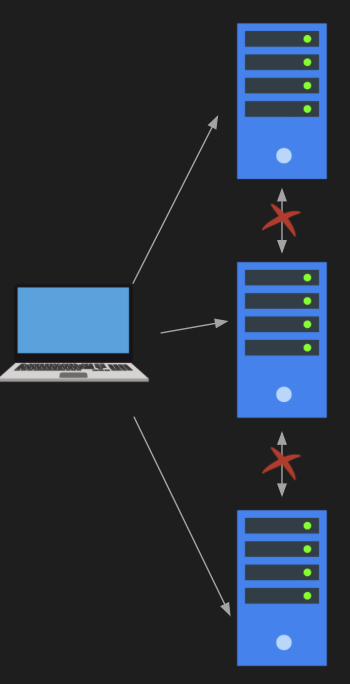

Distributed Cache

Memcached servers are isolated — servers don’t talk to each other. I absolutely love the simplicity and elegance of this design. If you want to distribute your keys, the clients have to do that, and you can build your own Memcached client to do just that.

Having servers communicate complicates the architecture significantly. Just like at zookeeper.

Telnet Demo

In this demo, we’re going to spin up a bunch of Memcached Docker instances. You’ll need to have Docker installed and have a Docker account because the Memcached image is locked behind an account. Once you do that, you can download the image, and you can spin up as many Memcached instances as you want. One thing to note is that Memcached does not support authentication, so you’ll have to implement authentication yourself.

The first thing we’re going to do is spin up a Docker container that has a Memcached instance. This can be done with the following command. We can add -d to avoid blocking the terminal.

docker run --name mem1 -p 11211:11211 -d memcached

Run docker ps to ensure that the image is running.

Let’s test it out with telnet. Run telnet husseinmac 11211 , replace husseinmac with your hostname. You should be logged in once this happens and can issue commands like stats.

We can also set key-value pairs in this console. For example, set foo 0 3600 2. foo is the name of the key, 0 is the flags, 3600 is the TTL, and 2 is the # of characters. Once you hit enter, it’ll prompt you for the value of the foo key. The value of the key should exactly match the # of characters that was set in the set command. The key-value pair can be read with the get command: get foo. It can be deleted with delete foo.

The interesting part of this demo is talking about the architecture of Memcached. You’ll notice that once you have added your foo key, you can type in stats slabs to get the slab statistics. You’ll see that there is one slab class (see STAT 1, the 1 represents the slab class). Additionally, you can see a lot of interesting statistics about chunks, pages, hits, the total amount of memory used, etc…

Distributed Memcached with NodeJS

To test the distributed cache, NodeJS provides a smart client that supports a pool of memcached instances. First let us connect to a single memcached instance from NodeJS and write a bunch of keys.

Create a folder for your project mkdir nodemem and cd into it. Then, initialize the project with npm init -y. Next, we’ll create an index.js file with the contents: Note: you’ll need to replace husseinmac with your hostname.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

const MEMCACHED = require("memcached");

const serverPool = new MEMCACHED(["husseinmac:11211"]);

function run() {

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9].forEach(a => serverPool.set("foo" + a, "bar" + a, 3600, err => console.log(err)))

}

run();

This piece of code uses the Memcached Node.js client and initializes a server pool of Memcached servers. Then, it adds a nine key-value pairs of the format foo1: bar1, foo2: bar2, etc… to the Memcached server pool.

Before running the script, we’ll need to install the Memcached Node.js client with npm install memcached. Then run the code with

node index.js

After the script runs, you should be able to telnet into the Memcached server and read the key-value pairs with get foo1, get foo2. All keys will be stored in the 11211 server.

Now, let us spin up even more memcached instances:

1

2

3

docker run --name mem2 -p 11212:11211 -d memcached

docker run --name mem3 -p 11213:11211 -d memcached

docker run --name mem4 -p 11214:11211 -d memcached

Once you start the containers, you’ll need to add the servers to the pool in your Node.js script:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

const MEMCACHED = require("memcached");

const serverPool = new MEMCACHED(["husseinmac:11211",

"husseinmac:11212",

"husseinmac:11213",

"husseinmac:11214"]);

function run() {

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9].forEach(a => serverPool.set("foo" + a, "bar" + a, 3600, err => console.log(err)))

}

run();

Once you run this script, you’ll notice that all the key-value pairs will be distributed to all 4 servers. Try it! telnet into the Memcached servers and run get foo1, get foo2, etc… to see which key-value pairs are where. This happens because the Node.js client picks one server in the pool to put the key-value pair based on its own hashing algorithm.

For reading, the NodeJS memcached client will do a hash to find which server has the key and issue a command to that server. Note that this hashing is different from the hash performed by memcached.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

const MEMCACHED = require("memcached");

const serverPool = new MEMCACHED(["husseinmac:11211",

"husseinmac:11212",

"husseinmac:11213",

"husseinmac:11214"]);

function run() {

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9].forEach(a => serverPool.set("foo" + a, "bar" + a, 3600, err => console.log(err)))

}

function read() {

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9].forEach(a => serverPool.get("foo" + a, (err, data) => console.log(data)))

}

read();

If you run this with node index.js, you’ll notice that all the values will show up despite not all Memcached servers having all the answers.

Summary

In this article, we talked about the Memcached architecture. We discussed the memory management and the importance to use slabs and pages to allocate memory to avoid fragmentation. We also talked about the LRU, which, in my opinion, should have been an option the user can disable. Next, we talked about threads which improve performance for high number of connections. We went through some examples of reads and writes with Memcached and how locking impacts them. Finally, we talked about the distributed cache architecture with a demo using Node.