Part 3: Database Engineering Fundamentals: MongoDB internal Architecture

MongoDB internal Architecture

androidstudio·December 12, 2022 (Updated: February 25, 2023)·Free: No

I’m a big believer that database systems share similar core fundamentals at their storage layer and understanding them allows one to compare different DBMS objectively. For example, How documents are stored in MongoDB is no different from how MySQL or PostgreSQL store rows.

Everything goes to disk, the trick is to fetch what you need from disk efficiently with as fewer I/Os as possible, the rest is API.

Here my tweet to a very common question I get that clarify the difference between SQL vs NOSQL.

In this article I discuss the evolution of MongoDB internal architecture on how documents are stored and retrieved focusing on the index storage representation. I assume the reader is well versed with fundamentals of database engineering such as indexes, B+Trees, data files, WAL etc, you may pick up my database course to learn the skills.

Let us get started.

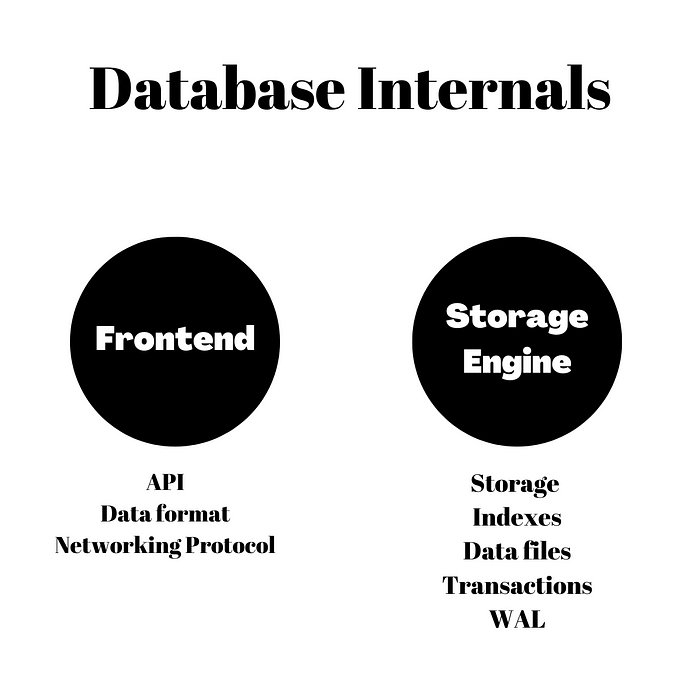

Components of MongoDB

In order to explore the MongoDB architecture I think it is important to understand some of the components of the database system.

Let us start by exploring the basic components in Mongo that I believe is relevant to our discussion.

Documents & Collections

MongoDB is a document based NOSQL database which means it doesn’t deal with relational schema-based tables but rather non-relational schema-less documents.

Users submit JSON documents to Mongo where they are stored internally as BSON (Binary JSON) format for faster and efficient storage. Mongo retrives BSON and cover them back to JSON for user consultation. Here is a definition of BSON from MongoDB

BSON stands for “Binary JSON,” and that’s exactly what it was invented to be. BSON’s binary structure encodes type and length information, which allows it to be traversed much more quickly compared to JSON.

Because documents can be large, Mongo can sometimes compress them to further reduce the size. Mongo didn’t always compress BSON and we will explore this later.

Users create collections (think of them as tables in RDBMS) which hold multiple documents. Because MongoDB is schema-less database, collections can store documents with different fields and that is fine. Users can submit document with a field that never existed any document in the collection. This feature is one that Mongo attractive to devs and it is also the feature that is abused the most.

_id index

When you create a collection in Mongo, a primary key _id representing the document id is created along side a B+Tree index so that search is optimal. The _id uniquely identifies the document and can be used it to find the document.

The _id type is objectId and it is a 12 bytes field. The reason it is large because Mongo uses it to uniquely identify the document across machines or shards for scalabilty. Read more about the structure of objectId here.

I also think the user can override the _id field with a value of their choosing which could make the key even larger. Keep this mind as we go through the article.

The _id primary index is used to map the _id to the BSON document through a B+Tree structure. The mapping itself has gone through stages as MongoDB evolved and we will also explore this.

Secondary indexes

Users can create secondary B+Tree indexes on any field on the collection which then points back to BSON documents satisfying the index. This is very useful to allow fast traversal using different fields on the document not just the default _id field. Without secondary indexes, Mongo has to do a full collection scan looking for the document fields one by one.

The size of the secondary index depends on two things, the key size which represents the field size being indexed, and the document pointer size. We will see that different versions of Mongo and storage engines makes big difference on that.

Now that we know the main components of Mongo, let us explore the evolution of Mongo internals.

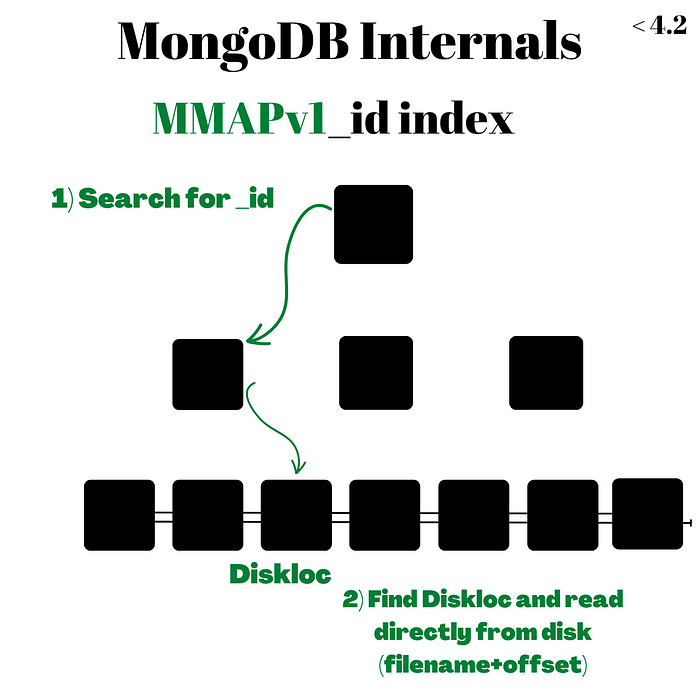

Original MongoDB Architecture

When Mongo first released, it used a storage engine called MMAPV1 which stands for Memory Map files. In MMAPV1 BSON documents are stored directly on disk uncompressed, and the _id primary key index maps to a special value called Diskloc. Diskloc is a pair of 32 bit integers representing the file number and the file offset on disk where the document lives.

When you fetch a document using its _id, the B+Tree primary key index is used to find the Diskloc value which is used to read the document directly from disk using the file and offset.

As you might have guessed, MMAPV1 comes with some of limitations. While Diskloc is an amazing O(1) way to find the document from disk using the file and offset, maintaining it is difficult as documents are inserted and updated. When you update a document, the size increases changing the offset values, which means now all Diskloc offsets after that document are now off and need to be updated. Another major limitation with MMapv1 is the single global databse lock for writes, which means only 1 writer per database can write at at time, signfically slowing down concurrent writes.

In this image you can see the leaf pages of the B+Tree are linked together for effective range scans, this is a property of B+Trees.

One index lookup is required in this architecture plus an I/O 𝑂(𝑙𝑜𝑔𝑛) + 𝑂(1)

Mongo did improve MMapv1 to make it a collection level lock (table level lock) but later depreceated MMapv1 in 4.0 in favor of WiredTiger, their new and default storage engine.

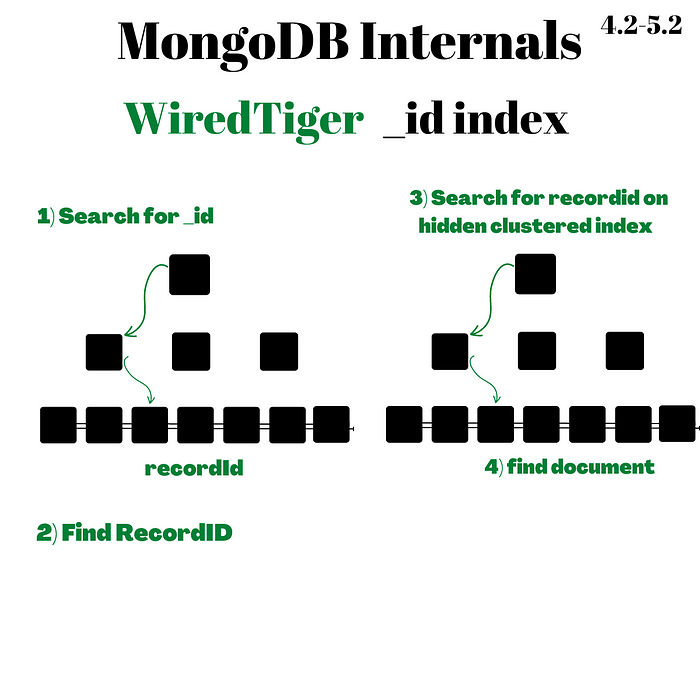

MongoDB WiredTiger Architecture

In 2014. MongoDB acquired WiredTiger and made it their default storage engine. WiredTiger has many features such as document level locking and compression. This allowed two concurrent writes to update different documents in the same collection without being serialized, something that wasn’t possible in the MMAPV1 engine. BSON documents in WiredTiger are compressed and stored in a hidden index where the leaf pages are recordId, BSON pairs. This means more BSON documents can be fetched with fewer I/Os making I/O in WiredTiger more effective increasing the overall performance.

Primary index _id and secondary indexes have been changed to point to recordId (a 64 bit integer) instead of the Diskloc. This is a similar model to PostgreSQL where all indexes are secondary and point directly to the tupleid on the heap.

However, this means if a user looks up the _id for a document, Mongo uses the primary index to find the recordId and then does another lookup on the hidden WT index to find the BSON document. The same goes for writes, inserting a new document require updating two indexes.

Two look ups are required in this architecture 𝑂(𝑙𝑜𝑔𝑛) + 𝑂(𝑙𝑜𝑔𝑛)

The double lookup cost consumes CPU, memory, time and disk space to store both primary index and the hidden clustered index. This is also true for secondary indexes. I can’t help but remember a blog article by Discord why they moved away from Mongo to Cassandra, one reason was their data files and indexes could no longer fit RAM. The storage of both indexes might have exacerbated their problem but I could be wrong.

Despite the extra I/O and double index storage for _id in this architecture, both primary and secondary indexes are still predictable in size. The recordId is a 64 bit which is relatively small. Keep this in mind because this is going to change one more time.

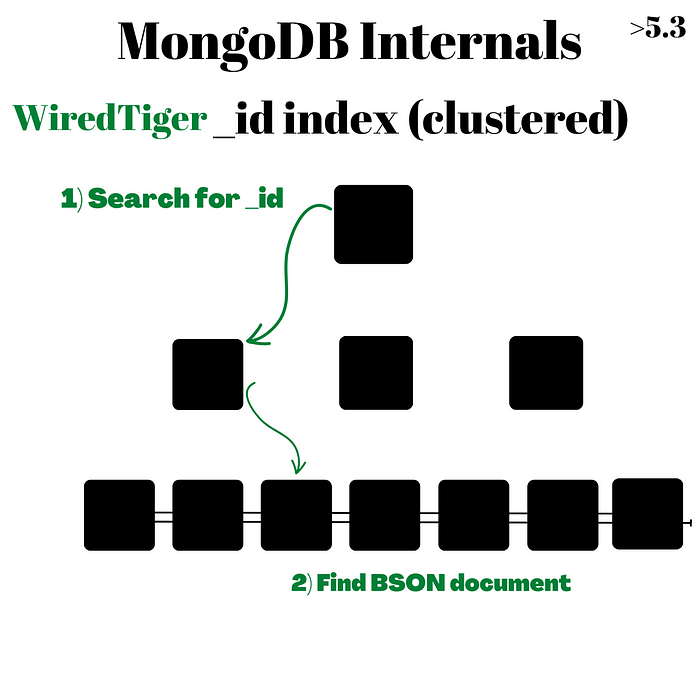

Clustered Collections Architecture

Clustered collections is a brand new feature in Mongo introduced in June 2022. A Clustered Index is an index where a lookup gives you all what you need, all fields are stored in the the leaf page resulting in what is commonly known in database systems as Index-only scans. Clustered collections were introduced in Mongo 5.3 making the primary _id index a clustered index where leaf pages contain the BSON documents and no more hidden WT index.

This way a lookup on the _id returns the BSON document directly, improving performance for workloads using the _id field. No more second lookup.

Only one index lookup is required in this architecture 𝑂(𝑙𝑜𝑔𝑛) against the _id index

Because the data has technically moved, secondary indexes need to point to _id field instead of the recordId. This means secondary indexes will still need to do two lookups one on the secondary index to find the _id and another lookup on the primary index _id to find the BSON document. Nothing new here as this is what they used to do in non-clustered collections, except we find recordid instead of _id.

However this creates a problem, the secondary index now stores 12 bytes (yes bytes not bits) as value to their key which significantly bloats all secondary indexes on clustered collection. What makes this worse is some users might define their own _id which can go beyond 12 bytes further exacerbating the size of secondary indexes. So watch out of this during data modeling.

This changes Mongo architecture to be similar to MySQL InnoDB, where secondary indexes point to the primary key. But unlike MySQL where tables MUST be clusetered, in Mongo at least get a choice to cluster your collection or not. This is actually pretty good tradeoff.

Summary

Database systems share the same fundamentals when it comes to their internal storage model. I really like this because it removes fluff and allows me to answer questions related to performance in a predictable manner. Marketing brochures where each database claims to be the best, fastest and scalable no longer has power on an engineer who understands the fundamentals.

In this article I discussed the MongoDB internal architecture evolution. In MongoDB the clustered collection is an interesting feature. However, one must use it with caution as the more secondary indexes the larger the size of these indexes get the harder it is to put them in memory for faster traversal. The MongoDB docs on clustered collection.

If you prefer to watch videos here is my coverage on my youtube channel

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ONzdr4SmOng

References

https://groups.google.com/g/wiredtiger-users/c/qQPqhjxyU00

http://smalldatum.blogspot.com/2021/08/on-storage-engines.html?m=1

http://smalldatum.blogspot.com/2015/07/linkbench-for-mysql-mongodb-with-cached.html

https://groups.google.com/g/mongodb-dev/c/8dhOvNx9mBY

https://www.mongodb.com/docs/upcoming/core/clustered-collections/#clustered-collections

https://jira.mongodb.org/browse/SERVER-14569

https://www.mongodb.com/docs/v4.4/reference/operator/meta/showDiskLoc/

https://github.com/mongodb/mongo/commit/374438c9134e6e31322b05c8ab4c5967d97bf3eb